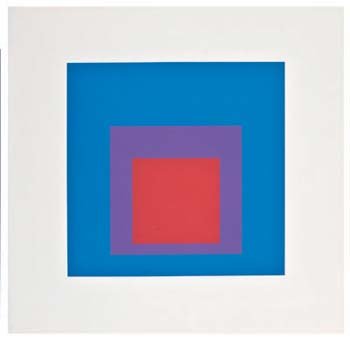

Homage to the Square: Full, from Ten Works portfolio

- 1962

- Josef Albers (German-American 1888-1976)

- Screenprint

28.0 x 28.0 cm., 11 x 11" image

- Gift of Josef and Anni Albers Foundation through Catherine Carter Goebel, Paul A. Anderson Chair in the Arts in Memory of James Konrad, Paul A. Anderson Art History Collection, Augustana College 2011.10

Essay by James Konrad, Former Adjunct Assistant Professor of Art and Catherine Carter Goebel, Editor

In teaching students about color theory, two lessons are indispensible: the nineteenth-century color wheel of chemist Michel-Eugène Chevreul and the Homage to the Square series by artist Josef Albers. In the former, the physics of light is delineated as a tool to teach component colors created through the breakdown of light. Chevreul's theories were essential to nineteenth-century art, particularly evident in the colorful works of French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Albers continued such experimentation in color theory through his Homage series. Inspired by Post-Impressionist, Paul Cézanne and further allied with the theories of contemporary, Piet Mondrian, Albers began this series in 1950 and continued exploring such "interaction of color" for twenty-six years. He aimed for "visual experience rather than psychological revelation or historical reference: the aspects of color and line and form, as well as of nature and man-made objects, that are universal and valid in any place and at any time" (Weber, Albers Prints).

Albers' design was based in the fundamental order of architecture and design, rooted in his early teaching in the Bauhaus school in Germany. His Homage to the Square series was the "ultimate achievement of his life" (Weber 7). Albers described these works in painting and prints, as "'platters to serve color.' They are hymns to the infinite possibilities, both physical and spiritual, of hue and light" (Weber 7). The series is based on a format of nesting squares, as illustrated in Homage to the Square: Full. These are weighted toward the bottom while centered left and right. There is order yet complexity as "the incremental distances underneath the central squares are doubled to left and right of them and trebled above" (Weber 8).

The conception upon first glance may appear deceptively simple. Yet there is a sort of magic that occurs that denies a singular interpretation. Albers stated: "In action, we see the colors as being in front of or behind one another, over or under one another, as covering one or more colors entirely or in part. They give the illusion of being transparent or translucent and tend to move up or down" (Weber 8). Take time to focus only on the center square in order to visually absorb the color. You will be rewarded with a transformative experience. "The interaction of colors is multifarious; perfectly flat areas appear shaded; the squares grow darker near one boundary and lighter near another. Nothing is as it seems" (Weber 8). Albers humbly concluded: "How far this has been successful is for others to decide" (Weber 9). As art and art history professors, and their students, have acknowledged for over half a century, and as viewers may discern, Albers' success is timeless.