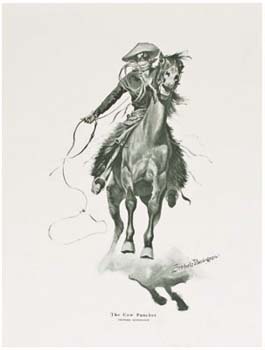

The Cowpuncher, or No More He Rides

- n.d.

- Frederic Remington (American 1861-1909)

- Lithograph, originally published as Collier's Weekly cover, 1901

40.2 x 30.2 cm., 15-7/8 x 11-7/8"

- Catherine Carter Goebel, Paul A. Anderson Chair in the Arts Purchase, Paul A. Anderson Art History Collection, Augustana College 2010.41

Essay by Jane Simonsen, Associate Professor of History and Women's and Gender Studies

Art historians have noted the gendered and racialized imagery of Remington's paintings: in this case, men with their guns pointed outward protecting themselves against a faceless, encircling enemy, even as one of their own assumes a fallen and "feminized" position. In this standoff between white men and native, it's unclear who will triumph; one man's gun even seems to be lowered, a sign that he was losing power. While a reading of Freudian imagery seems to be a stretch, when we consider that Remington's contemporaries believed that men's sedentary, indoor lives might lead to a loss of virility—a depletion of their "vital sources"—and that Roosevelt himself was deeply concerned with the possibility of "race suicide"—a declining birthrate among westernized nations as couples delayed marriage and limited numbers of offspring—this interpretation gains credence. The image of the encircling racial Other who would confine white men to a narrow sphere of influence impressed upon American men the necessity of proving themselves against such limiting and suffocating others—or die trying. The image of the cowboy such as The Cowpuncher (web gallery 176) that Remington and his contemporaries (illustrators like Charley Russell and writers like Owen Wister, author of the 1902 novel The Virginian) helped to create survived well into the 1960s, as screen heroes like John Wayne, James Stewart, and Henry Fonda re-enacted the conflict of men beset by civilization on the one side and savagery on the other. In such films, Native Americans represent the wild, untamed self that men both fought against and longed to be, while women often represented the alluring yet confining call of safety, domesticity, and familial duty.

Certainly viewers today recognize the messages about masculinity implicit in this image, for many are still present in our popular culture. As war drags on in the Middle East, work is outsourced to other countries, and young men find themselves outnumbered by women at colleges, we still look to images like this one to find meanings for manhood. Films like The Hurt Locker (2008) and 127 Hours (2010) suggest that dusty, foreign soils and harsh landscapes are still fertile grounds for forging a sense of self in the face of the ruthlessness of nature and the folly of boyish choices—but at enormous cost. We also confront the ironic masculinity of the Old Spice Guy, in which we're invited to mock definitions of manliness that are impossible to uphold. Men and women who viewed Caught in the Circle (web gallery 175) in 1914—when the U.S. was witnessing a devastating war abroad—may have wondered whether war in the trenches of Europe would bring about power or destruction. Likewise, young men today may wonder how to confront the pressures that surround them, and whether the traditional tools of masculinity can still work in a postmodern world. What does it mean to man up in the early 21st century? What are the rituals and experiences that confirm masculinity? Does becoming a man involve facing up to the responsibilities of work, school, and family, or is it only forged through a flight from such responsibilities, to face dangers where you either win or die trying?