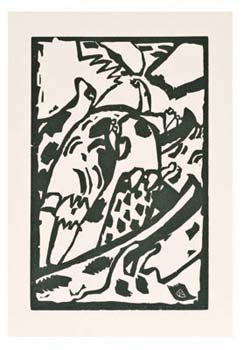

Improvisation 7, after the ca. 1914 paitning series

- 1976

- Vassily Kandinsky (Russian 1866-1944)

- Woodblock print

19.0 x 12.5 cm., 7-1/2 x 4-7/8" image

- Catherine Carter Goebel, Paul A. Anderson Chair in the Arts Purchase, Paul A. Anderson Art History Collection, Augustana College 2008.6

Essay by Robert Elfine, Associate Professor of Music

Though you may not know it, it is likely that you are a skilled improviser. Furthermore, it is entirely possible that you have participated in the process of improvisation at some time today, given that anyone who has ever been a part of an unscripted conversation has experienced a form of improvisation. By way of contrast, imagine a world where all communication was planned out in advance!

Simply put, to improvise is to spontaneously create with a minimum of planning or preconception. For most of us, this term is typically associated with music, though improvised poetry and theatre maintain active traditions of improvisation (slam poetry and improv comedy, for example). Furthermore, to Western audiences, the notion of improvised music calls to mind the style of jazz, due to its association with dazzling displays of virtuosic improvisation. However, every culture that produces music also produces some form of improvised music, and the relationship between improvisation (spontaneous creation) and composition (planned creation) within a culture can reveal a great deal about how its people regard the musical experience.

It is clear that Kandinsky has a typically twentieth-century European view of the notion of improvisation by the way in which he describes two of his creative methods and the importance he places on each. Of one category of work, for which he would use the term "Improvisation," Kandinsky describes as "A largely unconscious, spontaneous expression of inner character, non-material nature." Another method of creation, the "Composition," is described as "An expression of a slowly formed inner feeling, tested and worked over repeatedly and almost pedantically"(77). It is this latter method that held greater significance for Kandinsky, much in the same way that most musicians of his time would typically uphold the virtues of composition as superior to improvisation.

This woodblock print displays the result of Kandinsky's reliance on "unconscious, spontaneous expression." Though abstract, there are clear representations of natural objects as seen in the branches and leaves in the lower half of the work. Yet, the print as a whole has a playful quality to it, as if the artist was completely immersed in the sensation of intuitively filling a two-dimensional space-engaging in creation and reflection as a single activity rather than two separate processes.