Aufruhr or Uprising/Revolt, 1899, Von der Beck edition

- 1945

- Käthe Kollwitz (German 1867-1945)

- Etching, 1945 Von der Beck edition

29.5 x 38.1 cm., 11-3/4 x 12-9/16" image

- Art Department Purchase, Augustana College Art Collection, 1969.23

Essay by April Bernath, Class of 2010

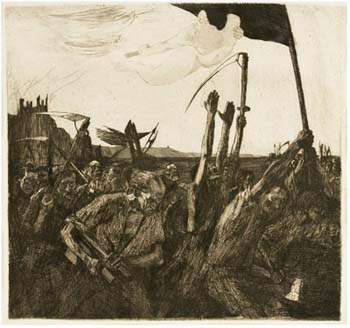

Tumultuously charging forward, the peasants in Käthe Kollwitz's Uprising, 1899 (Kearns 105), sweep the viewer up into the chaos. Through this interaction, one relates to the peasants' emotions-anger, fear and anguish line their angular, emaciated faces-and their cause. In presenting their distress, Kollwitz also expressed her early view of revolution and style.

The push for revolt against injustice in Kollwitz's pre-war image was a view held by many of her contemporaries (Moorjani 1110-1111) before the disillusionment of war was thrust into their lives. Clara Zetkin (1857-1933), a socialist leader, said: "We [women] are endowed with the strength to make sacrifices which are more painful than the giving of our own blood. Consequently, we are able to see our own [men] fight and die when it is for the sake of freedom" (Moorjani 1111).

This view is reflected in Kollwitz's print, in which an all-male mob is spurred forth by an allegory of revolution, an image reminiscent of artwork such as Eugène Delacroix's Liberty Leading the People (July 28, 1830), 1830 (Kearns 83). In Uprising, the allegory's hair blends into the flag; combining the personification into this banner makes her the essence of revolution.

As Kollwitz strove for Realism, she eliminated this Romantic allegory (Prelinger 33-34) and created the series Peasants' War (1899-1908) with the historical figure "Black Anna" from Historian Wilhelm Zimmerman's General History of the Great Peasants' War (1841-1842), in addition to her own conceptions of revolution (Prelinger 31, 33-34, 38). Peasants' War is the result of her thematic search, as started in Uprising (Prelinger 33).

Along with her adjustment in style, Kollwitz's view on revolution eventually was transformed into realistic terms. Six years after the creation of Peasants' War, her son Peter died in World War I (Moorjani 1114). Renouncing her earlier views, she reflected, "I have been through a revolution, and I am convinced that I am no revolutionist" (Kollwitz 100). Her Romantic notions of "dying on the barricades" were ruined because she had come to realize revolution's horrific consequences (Kollwitz 100). Though Kollwitz shifted from her Romantic view and style in Uprising, she would continue throughout her life to present the proletariat in her unique, expressive style.