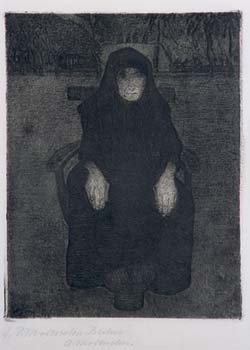

Sitzende Alte (Seated Old Woman)

- ca. 1900

- Paula Modersohn-Becker (German 1876-1907)

- Etching and aquatint printed in dark brown, state three of three

18.8 x 14.5 cm., 7-3/8 x 5-9/16" image

- Catherine Carter Goebel, Paul A. Anderson Chair in the Arts Purchase, Paul A. Anderson Art History Collection, Augustana College 2000.60

Essay by Heidi Storl, Professor of Philosophy and William F. Freistat Professor of Studies in World Peace

At the close of Part I of Nietzsche's Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche states: " .that is the great noon when man stands at the middle of his way between beast and overman and celebrates his way to the evening as his highest hope: for it is the way to a new morning" ("Thus spoke" 78). The artistic and philosophical connections between Paula Modersohn-Becker and Nietzsche are well-known (Diethe). Though Nietzsche died in 1900, Modersohn-Becker's artistic style continued to manifest the key themes of Nietzsche's philosophy for free spirits. Though Nietzsche claimed that free spirits did not yet exist, he maintained: "I see them already coming, slowly, slowly; and perhaps I shall do something to speed their coming if I describe in advance under what vicissitudes, upon which paths, I see them coming?—" ("Human" 6)

Nietzsche's free spirit possessed the "dangerous privilege of living experimentally" ("Human" 8). So, too, did Paula Modersohn-Becker. Not bound by customs and rituals, the free spirit, as exemplified by Modersohn-Becker, was free to create anew-to become master over self and virtue; to stand tall at the great midday and celebrate the possibility of a new dawn, a new way of life. What the free spirit sought—individually, daringly, and painfully—was a direct encounter (an "unmediated" encounter) with that which is. This is what others at the time identified as "Being."

Modersohn-Becker's Sitzende Alte (ca. 1900), like many of her portrayals of women, children, and peasant life in the often harsh Northern European environs, resonates with the essential form of being alive, of life qua life. Simplicity and elegance mix with desperation and beauty to form an incomplete vision of what life must have been like for her various subjects. Viewers are inevitably drawn into this incompleteness and forced to co-create answers: Was the old woman tired? Mourning? Fearful? Determined? Why are her hands so pronounced, why so large? Nietzsche, like Modersohn-Becker, understood the effectiveness of the incomplete: "Just as figures in relief produce so strong an impression on the imagination because they are as it were on the point of stepping out of the wall but have suddenly been brought to a halt, so the relief-like, incomplete presentation of an idea.is sometimes more effective than its exhaustive realization: more is left for the beholder to do, he is impelled to continue working on that which appears before him so strongly etched in light and shadow, to think it through to the end." ("Human" 92). Modersohn-Becker was aware of the risks she bore with her novel approach to a more authentic portrayal of what it was like to be. In a letter to her sister, she claimed: "I can see that my goals are becoming more and more remote from those of the family, and that you and they will be less and less inclined to approve of them.and still I must go on. I must not retreat. I struggle forward.but I am doing it with my own mind, my own skin, and in the way I think is right" (Witzling 199). To create anew-to become master over self and virture-that is Modersohn-Becker's goal in Sitzende Alte. This is also what Modersohn-Becker's great friend, Rainer Maria Rilke, honored in his famous Requiem for a Friend (1909): ".You set them before the canvas.and weighed out each one's heaviness with your colors..You let yourself inside down to your gaze; which stayed in front, immense, and didn't say: I am that; no: this is. So free of curiosity your gaze had become, so unpossessive, of such true poverty, it had no desire even for you yourself; it wanted nothing: holy" (Rilke 77).