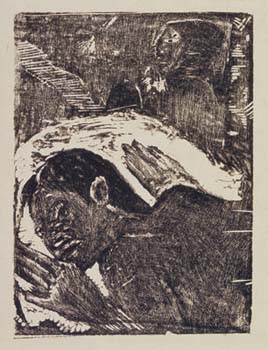

Manao tupapau (Spirit of the Dead Watching)

- 1894-1895

- Paul Gauguin (French 1848-1903)

- Woodblock print

17.3 x 12.8 cm., 6-3/4 x 5" image

- Catherine Carter Goebel, Paul A. Anderson Chair in the Arts Purchase with additional support from Art Exhibits and Gifts of Dan Churchill, Mr. and Mrs. George and Pat Olson, Mr. and Mrs. Al and Lynne DeSimone, and Dr. Kurt Christoffel, Paul A. Anderson Art History Collection, Augustana College 2004.8

Essay by Roger Crossley, Professor Emeritus of French

This woodcut is a variation on the theme of the tupapau (Spirit of the Dead) which Gauguin had already treated in 1892 in an oil painting with the same title during his first sojourn in Tahiti. Among several other versions of the tupapau figure were two (Te po [Night] and Manao tupapau) of a series of ten woodcuts which Gauguin made in 1893-4 for use as chapter illustrations in Noa Noa, his projected travel account of his first stay in Tahiti. This 1894-5 woodcut is similar to the original oil painting in that it depicts an (abbreviated) nude female figure lying on her stomach and peeking fearfully from the shelter formed by her upstretched fingers; the enigmatic figure of the tupapau looms behind her. In both oil painting and woodcut, the tupapau is a forbidding, hooded figure with a piercing almond-shaped eye seen against a shadowy background, although in the woodcut the tupapau is perhaps more menacingly placed almost directly behind the head of the nude woman.

Gauguin's woodcuts are innovative in both technique and subject. Though he may have drawn on a long tradition of French woodcuts or on a growing interest in Japanese woodcuts (web gallery 97 and 100) in fin-de-siècle France, Gauguin was a precursor of the revival of woodcuts in the early twentieth century (Goldwater 49).

As regards subject matter, Gauguin was no less a revolutionary. One might compare Gauguin's female figure (seen full length in the original oil-painting and in abbreviated form in the woodcut) with édouard Manet's Olympia (1863-web gallery 83), since in each case the figure is a reclining female nude. However, Gauguin's stated intentions in his letters and journals underline the differences between the Realist Manet and the primitivist, Post-Impressionist aspects of Gauguin's art. They suggest perhaps a greater affinity with artists like Pablo Picasso who drew much of his early inspiration from African masks and the Expressionists of the early 20th century.