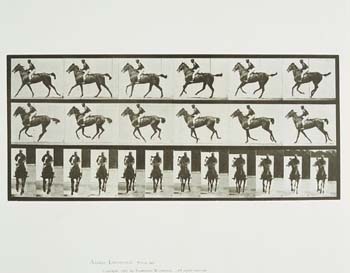

The Galloping Horse, Animal Locomotion. Plate. 621

- 1887

- Eadweard Muybridge (born England, American 1830-1904)

- Collotype

17.9 x 40.7 cm., 7 x 16" image

- Catherine Carter Goebel, Paul A. Anderson Chair in the Arts Purchase with assistance from the Reynold Emanuel and Johnnie Gause Leak Holmén Endwoment Fund for the Visual Arts, Paul A. Anderson Art History Collection, Augustana College 2006.18

Essay by David Freeman, Class of 2006

Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904) was an innovative nineteenth-century photographic artist who passionately pursued his obsession to freeze time and capture the body in motion. A British-born photographer, he advanced photography as a tool for demonstrating the mechanics of human and animal locomotion (Strosberg 225).

In 1872 the former California governor, Leland Stanford, had a question that he wanted answered through photography. Stanford believed that there was a point in a horse's gallop when all four hooves were off the ground and he wanted scientific proof of this. Muybridge unsuccessfully attempted to photographically document this action several times. However, by 1878 he finally succeeded in photographing a horse in fast motion (117A). Muybridge placed fifty cameras at equal distances along a track parallel to the running horse, controlled by a trip wire which, when triggered by the horse's hooves, set off the shutters in sequence as the horse passed. Each image was recorded sequentially at 1/200 of a second (Solnit 62).

Muybridge proceeded to take many photographic sequences of humans and animals in motion. People were often photographed doing various activities with little or no clothing (117B). These studies were undertaken in order to more accurately study the human body.

The images indicate an artist committed to the emerging culture of modern science-understanding through controlled observation and rational analysis of the world, using the potential of technology to surpass the limits of our own senses in order to enhance our powers of perception (Kerr 5-6). The proliferation and ubiquity of visual media today operates simultaneously with expanding technological precision in the production of visual tools. There is an unquestioned faith in, and reliance upon, the machinery of viewing, be it through the detail-capturing capability of digital cameras, the craze for high definition televisions, or the sophisticated computers and other machinery which allows scientists and physicians to see inside the human body (Barenscott 10). This reliance can be seen to originate with Muybridge.