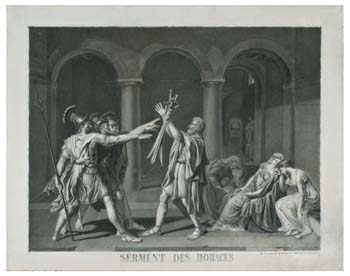

Serment des Horaces (Oath of the Horatii)

- 1815 drawing after 1784 original painting

- After Jacques-Louis David (French 1748-1825), draftsman undetermined

- Charcoal drawing

53.0 x 69.6 cm., 20-7/8 x 27-3/8" image

- Catherine Carter Goebel, Paul A. Anderson Chair in the Arts Purchase, Paul A. Anderson Art History Collection, Augustana College 2010.52

Essay by Katherine E. Goebel, Assistant Editor

Few painters have had the level of precision Jacques Louis David exemplified in his work. He possessed a rare ability to paint a story that enthralls the viewer into its historical narrative, while simultaneously pleasing the eye with its visual acuity. One of his most famous works, The Oath of the Horatii, painted in 1784, presents a theatrical scene from which much can be drawn. It was originally painted for King Louis XVI during an extended stay in Rome with his esteemed pupil Jean-Germain Drouais (Schnapper 73).

The story of the Horatii is one of tragedy and honor. Dating from 669 BCE, the cities of Rome and Alba were at war, the victor of which was to be decided by six choice warriors, three Horatii brothers from Rome and three Curiatii brothers from Alba. The heartrending spin to this conflict lies in the right side of David's composition, as the mourning women represent Sabina, a woman married to a Horatii and the sister of the Curiatii, and Camilla, engaged to a Curiatii and sister to the Horatii (De Nanteuil 90). Consequently, the viewer mourns for the women who will inevitably lose a loved one over a petty quarrel.

While the right half of the canvas occupies a feminine, emotional quadrant, the left, on the other hand, illustrates a sense of honor and valor as the three Horatii brothers pledge to their father their safe return, thus deeming the Horatii the victorious side. David was particularly vigilant about the portrayal of the warriors as their stance quite obviously dominates the composition, echoed by the three Roman arches in the background, whose blackness makes the oath stand out quite vividly. The three arches could also perhaps comment on the three levels of human emotion visible in the work. On the left, we see three brawny, determined men eager to please their father and defend their good name. In the center, we see Horatius, a father proud of his sons' loyalty, yet also anguished by the fact that their lives are at great risk. And, on the right, we view the women immobilized by dread and grief as they know they will soon mourn either a brother or lover's death (De Nanteuil 90). In this way, the three archways, divided by immense columns, precisely relate to the three levels of passion we recognize in David's figures (De Nanteuil 90). The Horatii brother in the forefront is based directly on artist Nicholas Poussin's seventeenth-century painting, Rape of the Sabine Women.

The juxtaposition of heroism and tragedy along with an immense focus on lavish drapery can be similarly seen in David's The Death of Socrates, 1787 (Schnapper 75). The overall tone of condemnation and vigor as the men prepare for battle is softened by the vulnerability of their loved ones. The shadow that bathes the background of the composition is likewise balanced by the soft hues that cover the figures in the forefront, again setting a stage-like scene from which the viewer can easily read the narrative.