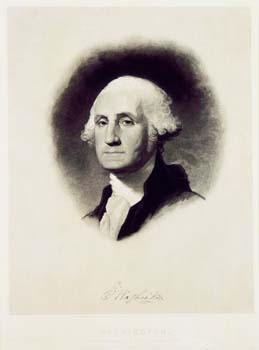

George Washington (The Athenaeum Portrait)

- After 1796 painting, 1852

- After Gilbert Stuart (American 1755-1828), by Thomas B. Welch (American 1814-1874)

- Engraving

67.2 x 50.6 cm., 26-1/2 x 19-7/8" image

- Catherine Carter Goebel, Paul A. Anderson Chair in the Arts Purchase with Gift of Adam J. DeSimone and David A. DeSimone, Paul A. Anderson Art History Collection, Augustana College 2005.23

Essay by Thomas J. Goebel, Assistant Editor, Class of 2008

This particular nineteenth-century engraving of Washington is based on Golbert Stuart's most famous portrait of the father of our country. The so-called Athenaeum Portrait was known during Stuart's lifetime as one of a pair of Mount Vernon Portraits (Miles 43), commissioned by Martha Washington to be hung at Mount Vernon in commemoration of Washington's retirement from public life. Unfortunately, however, Stuart never delivered the promised works, and instead kept them, making multiple copies of George's likeness for an endless number of responsive patrons.

Stuart rose to the challenge and effectively captured a straightforward depiction of the former general and statesman. The dark background, contrasted against the warm flesh tones, blue eyes and simple powdered hair, lent an air of intimacy and dignity to the composition. In this particular likeness, Washington posed to face the viewer's left, in order to balance Martha's mirrored position to the viewer's right, as it was anticipated that the two paintings would ultimately hang together. The squared jaw and bulge around Washington's mouth in this version were likely owing to a new set of dentures that the president complained to his dentist sat "uneasy in my mouth" (Barratt and Miles 152).

The real genius in this work rests in its balance of portraiture, a popular type of painting in America since Colonial times, and history painting, considered the most elevated form according to European academic standards. Artists like John Trumbull, one of Stuart's competitors, actively pursued history painting in the wake of the American Revolution, as in his famous image of The Declaration of Independence (web gallery 51). Although this work hung in the Capitol Rotunda, the market for large, expensive history paintings was more problematic in this new republic than in the traditional patronage system of European popes and monarchs. Stuart, on the other hand, shrewdly perceived that just the right portrait of the first American president could astutely blend the popularity of portraiture with the elitist status of history painting. In the Atheneaeum Portrait, he thus successfully combined the two in order to create an icon for American history.

This engraving, similar to those hanging in schools across America, is easily the most recognizable symbol within a flood of modern imagery. After all, what person in the United States has not held the minature of this image that is on every dollar bill? It was, and remains, the consummate image of promise and achievement for this country.