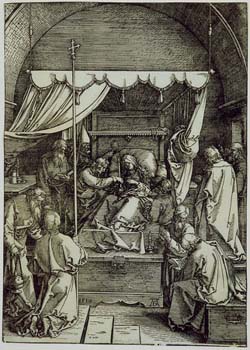

Death of the Virgin from Life of the Virgin

- 1510

- Albrect Dürer (German 1471-1528)

- Woodblock print

29.3 x 23.3 cm., 11-1/2 x 8-1/4" image

- Catherine Carter Goebel, Paul A. Anderson Chair in the Arts Purchase with Gift of Augustana College Art History Alumni in Honor of Dr. Mary Em Kirn, Paul A. Anderson Art History Collection, Augustana College 2003.7

Essay by Paul Bacon, Class of 1990

The 1510 Death of the Virgin was one of twenty woodcuts in Dürer's Life of the Virgin, which he published in book form for the first time in 1511. Benedictus Chelidonius, a Benedictine monk and member of the Nuremberg society of humanist scholars, joined Dürer in this enterprising venture, providing poems in classical Latin verse to accompany the nineteen narrative images in the series. It has been noted that the large, folio format with text and image opposite each other across the binding, as well as the high quality of Dürer's Life of the Virgin series and other religious prints, would have made them an excellent means for classroom instruction or for private devotional use (Hutchison 54).

The legendary account of the Virgin Mary's death and subsequent Assumption is drawn from various apocryphal books dating to the 2nd and 5th centuries. These earlier sources were condensed and popularized in the thirteenth century by a Dominican friar, Jacobus de Voragine, in his so-called Golden Legend. By Dürer's time, it was no longer customary for Death of the Virgin imagery to include Christ and the heavenly host at her bedside. In Northern Renaissance art, the Virgin Mary is generally shown holding a candle, in accordance with established Christian death ritual (Binski 33-47 and Wieck 109-119), which recommended placing a candle in the hands of a dying person as a symbol of his or her faith, as she rests on a canopied bed set within a domestic interior.

What set Dürer's composition apart from those of his predecessors was his innovative narrative style—in particular, his sophisticated use of one-point perspective (invented in the previous century) to draw in the viewer, to focus the eye on the central figure of Mary, and to map out the interior space in a clearly legible, realistic manner. Dürer employed a more sophisticated tonal system in his woodcuts, allowing him to impart an even greater sense of naturalistic light and shadow to the final three prints of his Life of the Virgin series, as we see here (Gunter 13).